The lengthy diary that follows was originally written in 2007.

Diary of a Graduate Thesis Experiment

The laboratory in which I am performing my thesis work (LAPD at UCLA) is used by researchers from all over the world. Groups that are using the device for a research project receive an allotted time in which to perform their experiment. Now is just such a time for me. My present data run extends from May 28 through June 2, 2007. This entry is an account of this run in the form of a diary-type schedule. I hope that this will demonstrate a little piece of the effort that is physics grad school.

Setup

The calendar start of a data run is simply the point at which you are allowed to use the machine. In order to have a successful run (i.e., to get a sizable amount of quality data) it is necessary to prepare well in advance. In this case I have been having meetings with my advisors on a mostly regular basis since our previous data run. These meetings set the priorities for the next run while progressing through the understanding of the existing data acquired.

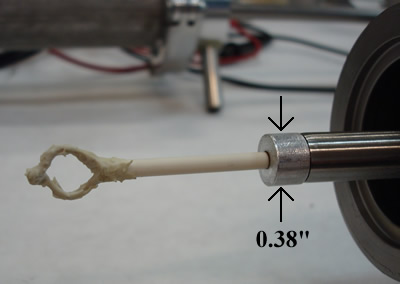

One area in which preparations well in advance were not possible is new probe construction. Past runs have demonstrated the need for more precision in the construction of probe tips, especially for the Janus and triple probes. These particular probes are much more straightforward to analyze when the tips are the same area. Making sub-millimeter tips by hand results in some area differences. I ordered some laser nickel pieces (shown at right), but they did not arrive until the Friday before the run. It usually takes a few days to make one probe. With the help of a fellow experimental plasma graduate student we were able to build four probes over the weekend. Whether these will work when we try to use them remains to be seen.

Skip to a Particular Day

Monday, Day 1 Tuesday, Day 2 Wednesday, Day 3

Thursday, Day 4 Friday, Day 5 Saturday, Day 6

Monday, Day 1

5:30 am – Wake Up

7:30 am – At the Lab, Finished Coffee

All of my data comes from physical probes placed in the plasma. These diagnostic tools must be carefully placed into the LAPD vacuum chamber (a write up of the construction process for one of these probes may be found here). As in other similar vacuum systems, inserting materials from outside the chamber requires pumping them down and then opening a valve to the main chamber. It takes about one hour to pump down a probe in the lab. Three separate probes can be pumped down at the same time, however, so it is generally a fast setup. The first accomplishment today is the pumping down of two Langmuir probes and one Bdot probe.

The electron beam, while not exactly delicate, requires careful conditioning and a slow startup. The beam used for my thesis is part of the general lab hardware and it is used in many other endeavors in which I am not involved. For this reason, lab personnel manage the startup of the beam. I try to be helpful by arranging the various items needed to run the beam. An operating setup is shown to the right.

The next item for beginning the experimental run is to prepare the data acquisition system (DAQ). This is the LAPD system that controls the position of probes, acquires their data (obviously), and then saves the data and other machine runtime information to a computer. I create a directory for this run and input some of the details such as which probes are being used.

11:00 am – Lunch

11:30 am – Fix Broken Probe

The best laid plans cannot account for every circumstance during run week. One of the probes I planned on using, arguably the most important one, broke last night. One of the outputs came loose inside of the probe and required it to be completely disassembled in order to be repaired. While the beam is being conditioned and it is not possible to start taking data yet, I decide to try and repair this probe.

12:15 pm – Check Machine Status

The first group of probes is opened to the main vacuum chamber and may now be aligned for DAQ control. Aligning the probes allows their position to be recorded by the DAQ. During a run, the DAQ will move a probe to a specified position within the plasma, record the data, and then move the probe to the next desired position. These movements are only accurate for properly aligned probes. Since my measurements require sub-millimeter precision I will take my time to align the probes. With these probes opened it is now possible to begin pumping out the fourth probe.

After the alignment, the probe outputs must be connected to electronics that will amplify and transmit their signals to the DAQ. Signals from these probes can be reviewed on an oscilloscope, which allows for an initial survey of the plasma column and electron beam performance (it has since been turned on and is emitting normally).

5:30 pm – Open Fourth Probe

6:00 pm – Begin Taking Data

All the preparations are complete and it is now time to begin running actual experiments. A “run” is a self-contained experiment. For example, a run may consist of collecting data across the plasma column for one value of background magnetic field. The next run could then be for a different magnetic field. Once begun, a data run is completely managed by the DAQ and the user (me this week) can sit back and wait until it is time to set up the next run. Usually, the results from one run dictate what is to be done for the following runs. It is typically the case that the user will have two data runs pre-planned so that the second one is underway during review of the first. After this, the third run is dictated by the results of the first, the fourth run is dictated by the results of the third, and so on.

12:00 am – Begin Overnight Run

Even graduate students have to sleep sometime, so a longer run is designed to take advantage of the overnight hours. Longer runs typically involve moving the probe (or probes) through a large plane of positions. It is easy to design a run lasting 8+ hours, and during my previous experiment week some runs took over 12 hours to complete.

12:30 am – Go Home

Tuesday, Day 2

5:30 am – Wake Up

7:30 am – At the Lab, Finished Coffee

During the day, my advisors come to the lab to review our status. We make parameter changes and perform manual probe scans (we do not manually move the probes, but we do input movement commands to the DAQ one at a time instead of programming a complete motion scan all at once). I continue to perform short data runs during the morning prior to the arrival of the advisors.

Once the advisors arrive it is time to begin searching. We are looking for interesting features of the probe signals. This manual scan helps to demonstrate that we are accurately repeating the physics results of previous work while simultaneously highlighting new or little explored behaviors. Data is viewed on an oscilloscope (see right, with a close up of the screen shown below) as these adjustments are made. We discuss the signals and formulate our continuing plan, essentially making small changes to the run setup that has been discussed during the time leading up to the run week.

12:00 pm – Lunch

1:00 pm – Continue Review with Colleagues

Throughout the rest of our examination of the experiment we prioritize the work that needs to be done. After deciding to try out the new probe (which was fully repaired yesterday) it is clear that pumping it down is at the top of the to do list. The rest of the afternoon involves adjusting circuits to improve signal output, reviewing the data collected thus far, and settling on an overnight run to be started after the advisors have gone home. While those actions are described in few words, they take six hours to complete.

7:00 pm – Perform Short Run

The plan for this evening’s overnight depends on a certain result. This result is determined by performing a short (≈ 2 hours) run. I need to complete this run, analyze the data (in a cursory manner, not publication quality review), calculate the parameter of interest (relating to the absolute position of a certain feature), and then setup the overnight run accordingly.

10:00 pm – Begin Overnight Run

The previous run provides the necessary information to program an overnight run. This information is incorporated into the overnight setup and begun. As a personal preference I like to remain near the lab for the first hour or so of the automated runs just to make sure everything is going smoothly. This time is passed by analyzing the existing data sets more carefully and printing out some of the results to share with my advisors. It is generally not as useful to have them looking over my shoulder at my computer screen. With printouts they can write notes all over the paper and even walk around the lab with it.

12:15 am – Check on Overnight Run

With a collection of printed out results it is time to check on the overnight run and then go home. Unfortunately, the overnight run has experienced an error and requires some effort to restart. This is the type of error that only stops the run, it does not have any detrimental effect on the machine. My efforts are not enough to revive the run and I am forced to wait for assistance from the research staff.

1:30 am – Sleep at Lab

At this late hour it is not worth it to drive home. Sleeping at the lab will actually allow me to get more rest by removing the round-trip commute time. I would have had to come in early in the morning to meet with the research staff anyway, so it is more efficient to hit the couch.

Wednesday, Day 3

6:00 am – Wake Up

6:30 am – At the Lab, Finished Coffee

7:00 am – Start Long Run

When the first staff member arrives, he is able to revive the overnight run in a matter of minutes. I discuss the issue with him at length and am prepared to follow the necessary steps should this problem resurface. This run is expected to complete in just over 8 hours. My morning is free and I seek to take advantage of it.

10:00 am – Go to Campus

For the sake of my advisors and everyone else at the lab (which is located at the southernmost edge of the UCLA campus), I go to the gym to take a shower. I have never worked out during a run week. Usually, the reason is that I am too tired and not motivated for physical exertion. At this moment I am also a little concerned about being dehydrated since I have had a lot more coffee and soda than water recently. It is unlikely that I would have wanted to work out even if I had been drinking water. A leisurely lunch in the student union follows the shower.

12:00 pm – Back at the Lab

The long run is going smoothly and a lot of data is being collected. An example of run monitoring is shown in the image to the right. From the control room it is possible to monitor both the machine performance and the data stream. The data is being written to the file as the run progresses, however, so it is not possible to perform analysis during a run. The data from each shot (the plasma pulses once each second) flashes up on a large screen. If something is wrong with one of the diagnostics it will be obvious, most likely seen as a flat line on this screen.

The advisors arrive and I update them on our status. We survey the existing batch of results and perform new manual scans. Final adjustments are made and it is determine to complete the remaining runs with the present state of electronics and diagnostic setup. Tonight’s run plan is agreed upon.

7:00 pm – Dinner

8:30 pm – Begin Short Run

The overnight run again depends on the result of a shorter run. This will take approximately two hours to complete. Once it is set up and begun, I need to find something else to do.

This is a good time to finish a write up (I use “write up” when referring to documents that I type up for passing around the group†) that my partner and I have been putting together. My partner is a graduate student in theoretical plasma physics here at UCLA. He works on the same physics as I do, though he concentrates on the theoretical treatment of it by using a computer code that models the experimental system and outputs predictions for what we should see in the measurements. His thesis also includes some details that will not be directly studied in the experiments, but we will both include material from the other in our theses.

A few email exchanges and some edits to the write up later, we are happy with the document and send out the group email.

11:00 pm – Begin Overnight Run

The shorter run has provided the necessary information to setup the overnight run. An unforeseen issue arises but is fixed within an hour. After monitoring the run for its first 45 minutes I determine that everything is operating well.

1:30 am – Go Home

Because of the late start, the overnight run will not be completed until nearly 9:00 am. Tomorrow’s plan is to test the recently repaired probe. No new runs will be performed until after the advisors have seen the new probe in action. This provides an opportunity to sleep longer this morning.

† The idea of sending preliminary results and experiment summaries to the group is an idea that was given to me by a fellow graduate student. She suggested typing up professional quality documents using LaTeX and then emailing pdf files to the group members. This is useful in multiple ways. First, it forces you, the writer, to clarify your thoughts and results into a coherent set of statements. Second, it leaves you with a collection of excellent notes that will prove useful over the few years (hopefully only a few) of your thesis study. Third, and finally, some of the items you write about are either going to be good enough for your thesis or at least good enough to serve as a first draft or outline for it. Already having the latex formatted material will save time when you start writing your thesis officially.

Thursday, Day 4

9:30 am – Wake Up

10:30 am – At the Lab, No Coffee

Last night’s run completed successfully. I take some notes about the run and begin testing the new probe. The most efficient use of machine time would be for me to have the probe tested and in a state that conveys its operating functionality to the advisors when they arrive. Signals indicate that the probe works, which in turn signals me that it is a good time to eat.

12:00 pm – Lunch

1:00 pm – Check Machine Status

None of the following discussion lends itself to picture taking, so here is a photo of the area of the lab where all my experiment equipment is set up. Once again, the plasma device is over 15 meters long so only a portion of it is seen in the photo.

A large power outage in the UCLA area affects the machine. Reports indicate that the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) is unable to supply power to areas of campus and the Westwood vicinity.

The LAPD has safety mechanisms in place that prevent such power transients and outages from causing catastrophic damage, but there is no backup power for actually running the machine. To run the machine requires several large power supplies that provide thousands of amps of current to run the magnetic field and plasma discharge. Such demands cannot be met with any backup systems (technically I am sure there are such systems, but they probably cost more than the rest of the lab combined). Systems that maintain device integrity can be backed up and they continue to function during problems originating within the LA power grid.

The machine, while preserved from significant damage, still requires some time to be returned to optimal operating parameters. Once the power problems appear to be over, the process of restarting the machine begins. This process is handled by lab staff and I occasionally peek in to try and learn more about the device and its inner workings.

4:30 pm – Resume Machine Operation

The plasma is back and we start to look around to assess whether the background conditions have changed. It is fortunate that we are in the lab because there is one more large power spike (I would hear later that traffic lights were out in Westwood and the UCLA Medical Center was running on emergency power) and the machine is again shut down. With staff already present in the lab, the machine is returned to operation within five minutes.

Review of the existing plasma resumes. It is determined that our experiment can continue without ill effect from the changes in the plasma. Basically, the changes that are observed are not relevant to the present experiment. The LAPD plasma is cylindrical with a diameter of approximately 70 cm and a length of over 15 m. Our effort is focused on an area that is a few square centimeters across over the entire axial length. We continue to work through the night and the staff will make some measurements tomorrow to determine any effects this might have on the research projects that follow our run week.

The advisors agree that the new probe is functional. This will provide the measurements for the overnight run. We settle on a plan and make the preparations.

8:45 pm – Begin Overnight Run

The overnight run begins and appears to be running smoothly.

9:30 pm – Dinner

10:30 pm – Check Status of Overnight Run

The run is still progressing smoothly. It is estimated to complete near 4:30 am, which makes the decision to go home difficult.

11:00 pm – Sleep at Lab

I decide that my commute time is better spent sleeping.

Friday, Day 5

4:30 am – Wake Up

4:45 am – Check Run Status

Last night’s run finishes five minutes after I arrive at the control room. With this early start time I am able to program another 8 hour run that will finish just in time for me to meet with the advisors and continue our effort.

6:45 am – Cancel Run in Progress

Some data needs to be acquired in order to quantify the state of the machine after yesterday’s power problems. The long run I had planned must be stopped. The data is still saved, though it is not a complete set that can be entirely compared with the other similar sets. A member of the LAPD staff begins taking data that will be used to judge the global state of the plasma.

10:00 am – Analyze Previous Overnight Run

Last night’s overnigh run featured a measurement that we have never made before. The resulting data from this run is of great interest and I decide to perform some detailed analysis that may direct the next long runs. The results are interesting and it is clear that the measurement itself was a success (i.e., the signal is really what it was intended to represent).

12:00 pm – Splash Data Around‡

I have made a few plots and left them on my computer screen for quick access any time an advisor inquires about the results. A broad review of the data set includes,

- Profiles – A display of any measurement as a function of space or time (e.g., the amplitude of a signal with the position of the probe as the x-axis).

- Power Spectra – The amplitude of various oscillation frequencies within the time signals.

- Raw Data – A few characteristic raw shot acquisitions provide perspective as to what the data looks like before processing through an analysis routine. This is always a good idea from the standpoint of double checking your results. For example, if your power spectrum shows a huge amplitude at some frequency, then your raw data should probably demonstrate oscillations with the corresponding period.

- Background Parameters – Plots of the machine status are useful for making sure that the system accurately reproduces the setup used for previous data sets. One of the main goals of this run is to measure certain behaviors as a function of background plasma settings. Before a unique looking result gets you too excited, make sure your plasma is truly the same as it was previously.

2:00 pm – Lunch

3:15 pm – Prepare for Next Runs

A review of the status data taken this morning reveals that the power issues from yesterday have affected the plasma. The effect is insignificant in the area where my experiment is being performed. After seeing this data, the leader of the research that is schedule to use the machine after my run week decides to reschedule for a time in which the plasma source will have been replaced. Source replacements are part of the standard device maintenance, so that group will not necessarily have to wait long for their machine time.

It is unfortunate that the next group is going to postpone their time. That means that their is no scheduled use for the machine after my official run ends. I am now able to extend this run into next week, probably until Wednesday.

We perform a two hour run, but it experiences a problem that delays its completion. In a brief moment of terror I smell something burning. It is a false alarm because the odor is the result of work being performed outside with the air making its way to the machine room, which is in the basement, by way of the air vents.

7:00 pm – Prepare Overnight Run

This might be the earliest that an overnight run has been started all week. The run should conclude at 3 am, at which time I would like to begin a similarly lengthy run. Everything appears to be running smoothly so I decide to go home for a few hours.

7:30 pm – Go Home

While the initial plan was to take a nap at home, upon my arrival I cannot sleep. I settle for some food and watch the SciFi Channel.

11:00 pm – At the Lab, No Coffee this Late

The overnight run is still going. Walking back to my desk I pass by the Electric Tokamak. Seen to the right, the tokamak is a little creepy during the late hours of the night. If you are interested in seeing a daytime photo of the machine with people standing on it for scale, then take a look at the ET Machine Site. I mentioned when I first got this camera, and the photograph below illustrates the problems I am having while learning about all of the available features.

The image to the left illustrates what happens when a photo is taken using the sensitive settings and a shaky hand. The camera accounts for low light levels (when set to the special low light/no flash mode) by keeping its shutter open longer. This means you need to hold the camera very still in order to get a good photograph. For this photo I thought the camera was done acquiring the image and lowered my hand. This generated the streak pattern.

1:00 am – Error Detected in Overnight Run

The overnight run has stopped due to a problem. It was 73% complete and cannot be resumed from its present position. This is a good example of why it is worthwhile to remain at the lab during an experimental run week. The data that has been acquired will be kept and I set up a new run that is only performs the pieces that this canceled run missed. After the setup time and a thorough check to ensure there are no larger problems lingering, this 2+ hour run is started.

After moving quickly to remedy the most recent issue I find myself energized and ready for more analysis. Unable to sleep, I begin Saturday work.

‡ The phrase, “data splashing” is attributed to the lab director of my first research group at UCLA. An accomplished member of the tokamak and fusion physics community, he was impressed by the ability of graduate students to analyze data on computers and produce colorful plots. Making a lot of such plots is splashing because it gets in everyone’s eyes and distracts from the job at hand. Those are not his exact words, which is why I have not put them in quotes, but that is fairly close to the exact statement.

Saturday, Day 6

2:15 am – Continue Data Review

At this point I am working to kill time until the run finishes. I open a remote window so that I can monitor the run’s progress from my desk.

3:30 am – Set Up a New Long Run

The previous run completes successfully. It is early enough to perform another long run that will complete before the advisors arrive. I watch it for ten minutes and the return to my desk. At my desk I review the remote monitor one additional time before deciding to rest.

4:30 am – Sleep at the Lab

The more tired you are, the more comfortable the lab couch becomes.

8:45 am – Wake Up

A phone call wakes me up. I make a mental note to turn off my phone next time I go to sleep, but then I realize it needs to stay on just in case the advisors call to adjust the schedule or get a status report. The remote monitor indicates the run has been going steadily. It is on schedule to complete near 1:30 pm.

9:30 am – Coffee and Pastry

A leisurely breakfast gives me a chance to read yesterday’s newspapers. Every once in a while I check the remote monitor.

There are fewer opportunities for taking photographs as the experiment week continues. In order to provide another reference for what the hardware setup I have included the image to the right which is from a run in October 2005. The blue glow is cause by an argon plasma (everything being done this week uses a helium plasma that appears orange in the photos and is not nearly as pretty looking). The well defined circular edge is caused by the cathode, which has been referred to previously as the plasma source.

Visible in the image are four probe shafts. The one coming in from an angle at the top right edge is the electron beam. It is pointed away from the camera so all we see is the supporting structure behind its source. The other shafts are Langmuir probes. While it may appear to be a crowded collection of diagnostics, these probes are actually separated by a few meters axially. Also, they are all measuring plasma parameters within a very similar radial extent of the cylindrical plasma column. The camera is positioned outside the vacuum chamber at one end of the 20 meter long machine (notice that previously I have mentioned the plasma column is over 15 meters long but the total vacuum chamber is longer because of all the support structure needed). The image distorts the position of the probes because of their different distances from the camera.

11:00 am – Monitor Run

I want to make sure there are no problems with the run. Our time may be coming to an end and we cannot afford to waste time due to run errors. While it would be great if I could continue high level data analysis, my concentration is beginning to wane. I type in a few commands for analysis and then read some news stories online. All of this while keeping an eye on the remote monitor.

1:30 pm – Check Run

The run completes successfully. I am free to go eat before meeting with the advisors.

2:00 pm – Lunch

2:30 pm – Making Adjustments

It is safe to say that the experiment week is now running efficiently. The advisors determine that we are in a good position to attempt an additional measurement. This particular measurement is non-perturbative as it involves optical measurements with the detectors placed outside of the vacuum vessel. Setting this up takes a decent amount of time. It works, but there is no connection to the DAQ so I will use an oscilloscope to save the data every run. Since I am doing it manually, I decide to save 50 shots for every individual run. These will be averaged and used to represent a typical behavior.

6:30 pm – Begin Overnight Run

Everything is underway for the next run. I acquire 50 shots of the new diagnostic from the oscilloscope. I write a large note to myself that will remind me to do this for all of the subsequent runs.

10:45 pm – Pirates of the Caribbean

By going to see this three hour movie I can guarantee that I will be awake when the run finishes around 2:30 am. The theater is two blocks away from the lab and the walk provides a good stretch. I am happy to spend the three hours without mention of ground loops, power supply shutdowns, and tangled BNCs, none of which are featured in the film.

Sunday, Day 7

2:30 am – Long Run Finishes

Three short runs must be performed before the next long run can be setup. The hardest part of these is waiting 40 minutes for them to complete. There are no errors and these short runs are eventually done, paving the way for another long run during which I will sleep.

6:00 am – Sleep at Lab

11:00 am – Wake Up

Waking up at this later time puts me in the mood for lunch. One microwave burrito later I am ready to get back to work.

The image to the right is a photo of the DAQ screen, hence the poor image quality. When this experiment week is over, a large collection of green checkmarks will indicate an efficient run. Some red X’s does not mean complete failure, however, because the data acquired up until the error is still saved. Some of the red X data sets will still provide for useful analysis.

The run names (corr5, etc.) do not mean much because I write thorough notes in my lab notebook. Some people make their run names very long and descriptive, including discriminating parameters and machine settings so that they can easily recall which runs include certain types of data. I just prefer to work with shorter file names.

1:30 pm – Long Run Completes

Another long run is in the bag. Four shorter runs are next in line and these will be followed by another overnight-type run.

6:30 pm – Go Home

This trip home consists of dinner, shower, and a long nap. I will go back to the lab before the long run finishes so that I can immediately begin new runs. Once Monday arrives there will be a constant chance that my time on the machine is over. With a full page of desired runs yet to be completed, I need to be as efficient as possible in acquired data.

Monday, Day 8

12:00 am – Arrive at Lab, No Coffee this Late

The long run will be complete in about another hour. I start working on organizing my notes. During the runs I find myself writing notes in my notebook and on any piece of scratch paper that is nearby when I think of something that needs to be recorded. At the conclusion of the run week I make copies of my notes for my advisors so that they know the details of the runs.

3:00 am – Prepare Long Run

I finished three short runs and am now ready to begin another 8+ hour one. This newest long run will finish some time near 12 pm, at which point I will begin preparations for follow up runs without actually starting them. The advisors will want to examine what we have so far before continuing.

What do we have so far? By this point I have written about performing analysis on data in between runs. While I cannot go into detail, I can provide some example images of what I am producing. The image below is one such analysis result in the form of a contour plot.

5:30 am – Coffee and Breakfast

I receive a coffee cup that leaks through the bottom. Possibly reaching my second wind, I return to data analysis. There is now a sizable set of results that we have had before.

12:30 pm – Long Run Finishes

Next in the list of runs is a set of two hour jobs. I receive word that our experiment time will go through this Wednesday. We already have a list of desired runs that will take us through that allotted time. Discussions with the advisors leads to a plan for this evening. The short runs will be completed by 6:45 pm. At that time we will move probes to different axial positions (the vacuum ports are separated axially, so this type of move requires removing the probe from vacuum and then pumping it down again in its new location) and let them pump overnight. While it is possible to have them ready within about an hour, by the time we get them moved and ready it will be late enough that all the lab personnel will have gone home. Only lab personnel can open vacuum valves on the machine. This is a precaution because if something goes wrong with the vacuum it takes one of the experts to prevent the plasma source from being ruined.

8:00 pm – Set of Shorter Runs Completed

8:30 pm – Begin New Idea Runs

The people authorized to open the machine valves have gone home. I can still work because there are two probes that remain open to the vacuum chamber already. My mindset is that I should continue to acquire data that will fill possible gaps in my thesis. To help myself figure out what these gaps might be, I try to imagine what questions my advisors will ask during my defense◊. An email from one of my advisors makes the decision much easier based on the questions it contains. I start to set up another series of short data runs to address this particular uncertainty in the experiment.

9:00 pm – Begin Fighting Ground Loop

Ground loops are the enemy of the experimentalist. These are basically problems associated with the electronics of an experiment and they result in everything from bad data (this loop was causing half of my data to appear upside down) to melted components.

10:00 pm – Ground Loop Destroyed

Now the first of tonight’s run series may begin. The short runs require less than 30 minutes to complete. I spend the rest of the night working on them.

◊ The defense is an oral presentation made to your thesis committee. In the UCLA Physics Dept. the defense is closed, meaning only you and your committee are there. The procedure is the same as the oral exam to advance to candidacy.

Tuesday, Day 9

6:00 am – Start New Run

It is almost too late to start a long run. I decide to compromise and setup a run that moves the probe to slightly fewer position than the other 8 hour runs. This will complete in 6 hours, which should have it finishing just in time to open the probes we moved yesterday.

6:30 am – Sleep at Lab

11:00 am – Wake Up

I decide to make a quick run to the gym so that I can take a shower. As before, I think my advisors will appreciate this.

12:30 pm – Work with Advisors

We set up the probe that was opened to the chamber this afternoon. After a little time performing manual scans we agree on a set of data runs that will take us through to the end of our machine time.

The plasma environment wears on materials placed within it. When a probe is removed from the chamber it is necessary to examine it and determine whether it has been damaged. If so, it does not need to be fixed right away but I do need to be aware of the problem so that I can fix it before it needs to be used again. The image to the right is of the Bdot probe that was recently removed from plasma operation. This probe consists of copper loops encased in epoxy. I expected to see the epoxy would be darkened as it is cooked by the plasma (the 50,000 °C plasma). As the image shows, there is no obvious damage. During the clean up process at the end of our time on the machine I will examine all the other hardware.

3:00 pm – Begin Long Run

The most important run of the set we still wish to perform is begun first. This should finish some time around midnight. The plan is for me to be rested by the time this finishes so that I can setup as many shorter runs all the way until I am asked to stop using the machine.

3:45 pm – Lunch

During the experimental run week cost is not a factor when it comes to eating. I have gone out for nearly every meal since beginning my time on the machine. It is worth it to spend more money on food because a successful run is priceless. In that regard, I would like to make mention of the best pizza in the UCLA/Westwood area. Enzo’s is 2 ½ blocks from the lab. They have pizza by the slice, but I have eaten the stromboli every time I went in this week. If you are visiting UCLA and want a taste of grad student life, then this is the place for you.

After a hearty lunch I spend the rest of the afternoon chatting with the other graduate students in the LAPD office space. We like to trade stories about issues that arise in the lab (I hope my ground loop story might be useful someday). The long run completes after midnight.

Wednesday, Day 10

12:00 am – Begin New Run

I want to begin a final run some time later this morning. Runs that are about half as long as the previous one are designed. Two of these can be completed before 8 am, leaving just enough time to perform one new measurement before cleaning up. Today is the last day for this experiment.

4:00 am – Sleep at Lab

The second of this early morning’s runs is begun, leaving a three hour sleep window.

7:00 am – Wake Up, Get Coffee

8:00 am – Begin New Runs

Today will consist of a new measurement, one that I have never even tried in previous experimental sessions. A member of the research staff shows me how to set this up and then I program a long run. There is a group scheduled to use the machine after my time concludes. By programming a long run I am basically agreeing to stop the run short whenever the next users are ready to begin changing the machine. This is an acceptable situation because 1) I already have a ton of data from this run, thereby making it a success, and 2) whatever data comes in before I stop the run is still saved and can be analyzed.

10:00 am – Begin Final Run

6:00 pm – Final Run Concludes

As the final run completes its very last steps the lab is already full of activity. Some people are preparing for the next big experiment while others are setting up tests for new measurements in hopes of debugging them before receiving their official lab time.

My own clean up procedure involves removing all the probes I was using and putting away all of the electronics. The BNCs I had strewn across the lab are coiled up and hung on their racks while all the BNC connector pieces are neatly placed back in their drawers. Some administrative work is necessary, such as transferring the remaining data files to the server in our office space.

7:30 pm – All Done

I have cleaned up all my equipment and the lab is already in use by others. The final stats for this run are:

- ≈ 70 separate data runs

- ≈ 77 GB of data (an overestimate because some of the data is stored in multiple formats)

- ≈ 200,000 plasma shots

- Confirmed functionality of two newly constructed probes (never had time to try the other two newly built probes).

- Didn’t get shocked once, which is quite an accomplishment for anyone working on a plasma experiment.

Conclusion

I hope this entry serves as a useful example of what it is like to perform a plasma physics experiment as a graduate student. It is a lot of work, but also a lot of fun.

I really can’t exaggerate about how thankful I am for your diary!